Services

Talk Therapy

I conduct psychotherapy with individual adults. My therapeutic orientation is psychoanalytic in nature. It is both how I practice, and how I understand humans and our suffering. It’s the type of therapy you most often see portrayed in movies and television.

Psychoanalysis, or talk therapy, was invented by Sigmund Freud in the 1890’s. Early on, he adopted a term coined by a patient to describe the mechanism of action in his therapeutic process – the “talking cure”.

Practically, this means that we sit together and talk, share feelings, and notice when you have symptoms in your body (e.g., sensations that seem related to the content, pain, fatigue, numbness etc.). We talk about what troubles you and brought you to treatment, we talk about what you want out of your life or about your difficulty in being able to distill that, and we talk about your life experiences and how they inform your contemporary sufferings, relationships, and thought patterns. The directions for patients in talk therapy are simple. We come to some agreement on what brings you to treatment, and then you talk about what is on your mind, and we go from there.

Through words, ideas, sensations, thoughts, and feelings, we make sense of your internal world and the difficulties that bring you to the consulting room and to seeking out a psychotherapy. It is by voicing what goes on inside your head and body, that we psychoanalytic therapists believe that suffering is lifted. This process is both powerful and efficacious.

EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing)

During a psychotherapy with a very well therapized patient, I found myself unable to gain much headway in helping them to resolve symptoms. They knew their issues; they had good insights into how their life history informed their development and the way their mind worked; they had had good treatment prior to meeting me, and yet their suffering across multiple domains persisted.

My work with that patient convinced me that there are some experiences that simply can’t be put into words. In 2009, in an effort to help them, I sought out training in EMDR. The new modality proved transformational for us both. Enduring symptoms began to abate, longstanding painful relationship patterns began to shift, and their life and relationships became fuller and more satisfying than at any other time in their life.

Created by Francine Shapiro in the 1980s, EMDR was initially crafted as a treatment for victims of violence and for people that experienced trauma more broadly. Subsequently, EMDR was found to be useful not only in healing painful memories and content, but also beneficial in strengthening positive emotions and experiences; and in facilitating peak performance of a task or activity. Unlike talk therapy, where the aim is to use words and emotions in the service of growth and healing, EMDR doesn’t rely on words as the mechanism of action. It is manualized and a more directed process than talk therapy.

When beginning an EMDR session to reprocess something that is troubling to the patient, we select something on which they want to work – this is called a target. An EMDR target might be an experience, a negative bodily sensation, an intractable emotional state, or a troubling idea or thought. Anything that conjures a negative emotional charge when it is called to mind is a suitable subject for EMDR treatment.

Once a target is known, we identify if there is an image that represents the topic at hand, the emotions that accompany the topic, the bodily sensations that arise from considering the content, and a negative idea that is generated from the target. Once those items are identified, the patient is asked to hold them in mind, and then I administer bilateral stimulation (BLS).

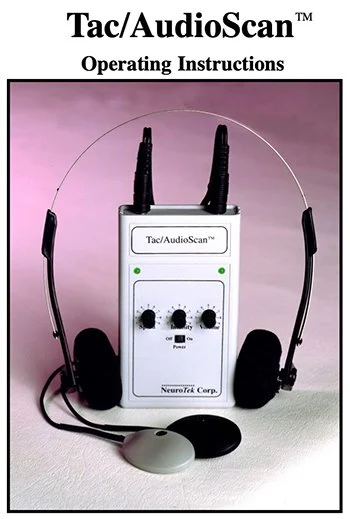

BLS is jargon for sensory input that alternates from one side of the body to the other. In the early days of EMDR, we used eye movements as bilateral stimulation. The therapist sat opposite and to the side of the patient. While the patient held their head still, the therapist moved their hand back and forth through the patient’s full range of vision, and the patient followed the therapist’s hand with their eyes. While eye movements are still used, it is more common to use headphones that administer an alternating beep, and/or “tappers” – small plastic disks that the patient holds in their hands, while they vibrate in an alternating fashion between the left and right hand. The sensation is much like that of a cell phone vibrating. BLS is pleasant and most people experience a sense of calm from its administration alone.

While BLS is underway, the directions to the patient are simple. You notice what you notice. Patients might have memories of the target being worked with, memories of associated material, emotions may surface, bodily sensations may present themselves, or ideas and thoughts may come to the surface. Periodically, I pause BLS.

During BLS breaks, the patient reports to me what they noticed during the BLS interval. Some people describe the experience as like being on a train, and watching scenery go by. Others experience the process as like watching a movie. Depending on the content, BLS might be started again, and the patient continues the processing, noticing what spontaneously presents itself. At other times, I provide prompts to the patient, or return their attention to the selected target at hand before resuming BLS. The sequence of BLS, pausing BLS, and reporting content continues repeatedly until the negative charge of the selected target goes away – and becomes neutral.

We know an EMDR target is completed (“reprocessed”) when it subjectively feels neutral, and when there has been some type of new learning or information generated about the target. EMDR doesn’t make painful content feel good or positive. It makes it neutral. It makes it feel as if it is in the past. It transforms traumatic memory, and powerfully negatively charged content, such that it subjectively feels more like other memories. In the words of many patients, “…it just doesn’t matter that much anymore…it’s over…it’s in the past…I don’t really want to think about it anymore…”. That is how we know when a target has successfully been cleared.

Many folks are drawn to EMDR because it both works and is known to work quickly. Reprocessing might be done in a single session or take multiple meetings before neutrality is achieved. The fastest I have ever had a target clear was 10 minutes, and the longest I have ever worked with a patient on neutralizing a target was 15 months. Both of those cases are extreme examples, and in the latter one, we took breaks from EMDR for weeks at a time. The work can be intense, and sometimes we need to put things away for a while, before deciding to resume reprocessing. While inexact, I would estimate that most targets take 2-6 sessions to clear entirely.

Single incident traumas that were experienced in adulthood clear most quickly. Repeated childhood traumas, or patients who have had multiple traumatic experiences across their lifespans, take longer to heal.

Patient Consultation

If you are new to treatment, if you have had other treatments that fell short of your needs, or if you are in a treatment that doesn’t seem to be going very well, I offer consultations. In these consults, we would speak some about your history, what leads you seek out help, and a bit about the type of psychotherapy that would best suit your personality and therapeutic aims. Consultations for treatment take 1-3 sessions and usually end with me providing you with the name of a colleague.

Professional Consultation and Supervision

I provide professional consultation to colleagues and students of mental health. To those looking to level up your work, I offer help. People come to me when they find a particular case troubling, intractably hard to help, or are concerned about a patient’s potential for suicide or homicide. At times, these consultations are single sessions in which there is a clear question needing exploration, a treatment plan needing the endorsement of a colleague, or a pernicious symptom that simply will not resolve. In my experience, though, colleagues usually present for a series of consultations, and seek to learn something new in their craft.

Trauma-informed treatments; risk and liability assessment; heterosexual colleagues learning to work well with queer populations and/or white clinicians learning to be able providers to black, brown, and Asian folks are all reasons people have sought out training with me. I also have extensive background in working with elders, those patients who experience sexual dysfunction, pain/conversion disorders, and those presenting with eating and feeding disorders.

I have also been called upon to help dyads -- therapists and patients where there are questions of a treatment being iatrogenic (someone seems to be getting worse) or deeply stuck. In these cases, I usually meet separately with both the patient and provider, and then make recommendations to both parties. Most often, this consultation leads to a new piece of work needing to be undertaken by the pair. At times though, I recommend ending the treatment, and refer the patient to a new provider, a new modality, or a new treatment milieu.

Adjunctive EMDR Treatment

At any given time, I have a few people in my practice that have a primary psychotherapist but also come to me for EMDR. Patients in concurrent Psychoanalysis or cognitive-based therapies are most often referred to me. In these cases, there is nothing unfortunate happening in their existing work, but there is some experience or symptom that isn’t being adequately treated. This work is always undertaken in careful consultation with the primary therapist and/or psychiatrist. The length of time in adjunctive therapy is widely varied, and is driven by what is being addressed, and the idiosyncratic history that any particular patient possesses. On average, I end up seeing folks for adjunctive treatment for three to six months. In cases in which people have a robust history of trauma, I have worked with them longer.